Did you know the PC Engine was the first console to have turbo buttons built into its official gamepads?

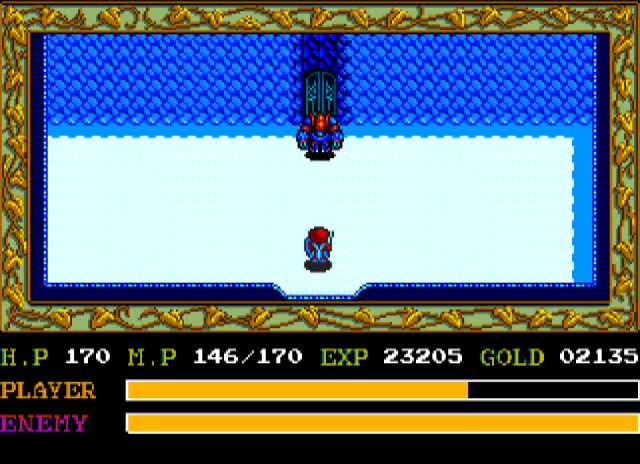

This is the honest solution: stand in front of Druegar and flip the I button to turbo. This boss was not correctly balanced. It takes more damage than it dishes out, which is something that will come up again with another Ys II boss. Even without turbo buttons, some rudimentary button mashing will win the day.

The intended solution for taking down the big spider is to build on the Velagunder strategy, positioning oneself just within its radius and mashing the magic button to spam spells into it. Between bouts of this the player is supposed to shadow the boss' movements, making quick but precise adjustments to line up their shots. It doesn't matter because you can, with very minimal movement in the international versions, just spam the Fire button and win a fifteen-second damage race. Sure you'll end the fight with a sliver of HP left, but so long as you have at least 1 point remaining when the last shots are fired, you'll get it all back when Druegar goes down.

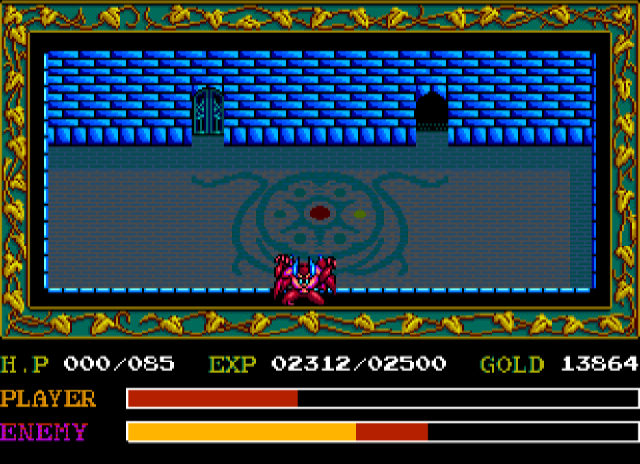

It would be sad coming off of Gelaldy, but this boss doesn't happen that fast. See, the second half of Ys II is a remarkable shift from the first: it takes place entirely within the confines of the Solomon Shrine, so just put this track on loop for three hours straight and you'll have an idea of what the endgame's like. It involves constant backtracking, and alternating between human and animal form to solve puzzles and defeat monsters--which would be pretty nice if it didn't leave you underleveled for Druegar. Visually the environments do show more variation, with the dark gates of the shrine giving way to the murky sewer making up its underground canal, and the pearly austerity of the goddess palace, but the soundtrack doesn't reflect any of this. This is where the combat system being so repetitive harms Ys I & II the most, as it falls on the sound design to carry the aesthetic experience of the game, and that loop just isn't enough.

The second half of Ys II does capture the feeling of subterfuge and stealthily moving around an enemy encampment, but it does so without the same progress metrics found in the first game's dungeons, and without respect for the player's time. The Shrine is a slog for the sake of being a slog, populated with key items that are used once and then forgotten, and because these markers serve as the player's only measure of progress, they lack a defined sense of advancement as they go through the dungeon. So the issues with this arc of the game aren't limited to something as simple as rebalancing Druegar, it's an issue with the structure of the endgame, with the player having to constantly warp back to locations and return to different parts of the dungeon.

Yet while Druegar was easy to the point of mindlessness, the boss that follows is an exercise in frustration...

Friday, April 26, 2019

Thursday, April 11, 2019

Designing Ys II, Vol. 3: Gelaldy

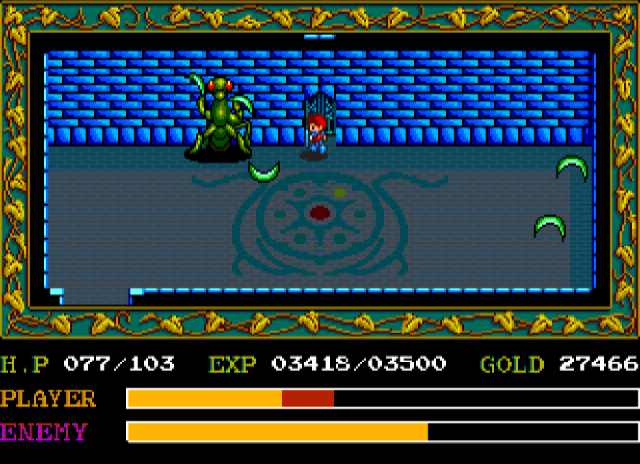

Among the seven bosses of Ys II, Gelaldy stands out for being the most polished. Velagunder was boring and Tyalmath underwhelming, and the boss immediately after Gelaldy is downright embarrassing. But the boss of Burnland/Burnedbless has a distinct attack pattern that meshes well with the magic system and creates phase-like sequences of interaction with the player. It's not a multiphase boss in the Dragonlord sense, but just slightly more complex than the likes of Nygtilger and Khonsclard.

So why does Gelaldy work? The fight begins with the big green guy simply chasing the player around the arena, immune to both physical and magical attacks. After the player leads him on long enough, Gelaldy will stop and heave up a tapeworm, causing the player to now be pursued from two different angles. After evading the tapeworm for a bit, Gelaldy will recall it and loop back to the beginning of his pattern.

The key is that Gelaldy's points of vulnerability are when he is either spitting up or horking down his worm. At any other time the Fire spell will simply bounce off of him, while at these moments the player can blast away at the big beheaded beast. This property is what creates the fight's victory sequence; the player evades, then fires while Gelaldy is setting the worm up, evades again, and then fires when he's taking it out of play. Mechanically it follows a pattern in Ys II—Velagunder was vulnerable after attacking and Tyalmath immediately before, now Gelaldy is vulnerable both before and after his attack sequence. Having a sequence to the fight makes it more engaging for the player than Ys II's previous bosses, as it gives them cues to pay attention to and something to plan for during the moment-to-moment play. It's no Dark Fact, but you're always watching for that opening while going up against Gelaldy.

On a broader level, Gelaldy represents a kind of threshold in the gameplay of Ys II. Every Ys boss takes place before a doorway that represents some kind of major change, whether that's acquiring new information through a Book of Ys or even traveling to the land itself. The journey up to the point of fighting Gelaldy has been about ascending up towards the peak of the island, while the journey after is about saving its people and undoing the hundreds-year-old circumstances that placed it in the skies of Esteria. There's not any particular deep significance in what he is as a monster, but it's important that this boss leave an impression on the player as they're going between these two components of the storyline.

(Also of passing interest is that this specific section of Ys II seems to have impacted Toby Fox's Undertale. He's already listed the music of the duology as influential, but the PC Engine/TurboGrafx version's Burnland and the later Ys Core areas seem to have influenced Hotland and the CORE in Undertale.)

Count your lucky stars that this boss turned out so well. Boss #4 is frustrating in an entirely different way...

So why does Gelaldy work? The fight begins with the big green guy simply chasing the player around the arena, immune to both physical and magical attacks. After the player leads him on long enough, Gelaldy will stop and heave up a tapeworm, causing the player to now be pursued from two different angles. After evading the tapeworm for a bit, Gelaldy will recall it and loop back to the beginning of his pattern.

The key is that Gelaldy's points of vulnerability are when he is either spitting up or horking down his worm. At any other time the Fire spell will simply bounce off of him, while at these moments the player can blast away at the big beheaded beast. This property is what creates the fight's victory sequence; the player evades, then fires while Gelaldy is setting the worm up, evades again, and then fires when he's taking it out of play. Mechanically it follows a pattern in Ys II—Velagunder was vulnerable after attacking and Tyalmath immediately before, now Gelaldy is vulnerable both before and after his attack sequence. Having a sequence to the fight makes it more engaging for the player than Ys II's previous bosses, as it gives them cues to pay attention to and something to plan for during the moment-to-moment play. It's no Dark Fact, but you're always watching for that opening while going up against Gelaldy.

On a broader level, Gelaldy represents a kind of threshold in the gameplay of Ys II. Every Ys boss takes place before a doorway that represents some kind of major change, whether that's acquiring new information through a Book of Ys or even traveling to the land itself. The journey up to the point of fighting Gelaldy has been about ascending up towards the peak of the island, while the journey after is about saving its people and undoing the hundreds-year-old circumstances that placed it in the skies of Esteria. There's not any particular deep significance in what he is as a monster, but it's important that this boss leave an impression on the player as they're going between these two components of the storyline.

(Also of passing interest is that this specific section of Ys II seems to have impacted Toby Fox's Undertale. He's already listed the music of the duology as influential, but the PC Engine/TurboGrafx version's Burnland and the later Ys Core areas seem to have influenced Hotland and the CORE in Undertale.)

Count your lucky stars that this boss turned out so well. Boss #4 is frustrating in an entirely different way...

Wednesday, April 10, 2019

Designing Ys II, Vol. 2: Tyalmath

Like Velagunder before it, the second boss of Ys II is invulnerable to physical attacks. After completing their descent into the Mines of Ys and their subsequent ascent through the Ice Park, the player solves a brief illusion puzzle and finds themselves confronted by a monster that casts fire magic of its own.

While Velagunder had to be attacked immediately after firing, Tyalmath instead requires the player to take advantage of an opening just before he attacks rather than right after. (In practice the boss is vulnerable both before and after, but if the player wants to survive then they need to shoot first at least once.) Similar to Dark Fact, the difficulty of the fight comes from Tyalmath being able to fire in eight directions while the player can only do so in four. It also comes from Tyalmath having something the player doesn't—being able to bump. The player now feels the full weight of losing the original combat mechanics, as Tyalmath tries to simultaneously shoot them down with fireballs and chase them around the arena to ram them into the snow.

The most interesting aspect of the fight is how Tyalmath uses perspective to convey the illusion of depth, jumping up "towards" the screen and becoming bigger or smaller depending on how close he is to our own world. It's an impressive visual effect even on the original PC-88 hardware, but it also betrays something about Ys II: this game is much more an aesthetic showcase for the computers and consoles it was published on than it is a mechanically sound game. This is far from the last boss in Ys II meant to show off hardware power, but it is one of the more blatant.

Fortunately, boss #3 marks a significant upswing over what came before.

While Velagunder had to be attacked immediately after firing, Tyalmath instead requires the player to take advantage of an opening just before he attacks rather than right after. (In practice the boss is vulnerable both before and after, but if the player wants to survive then they need to shoot first at least once.) Similar to Dark Fact, the difficulty of the fight comes from Tyalmath being able to fire in eight directions while the player can only do so in four. It also comes from Tyalmath having something the player doesn't—being able to bump. The player now feels the full weight of losing the original combat mechanics, as Tyalmath tries to simultaneously shoot them down with fireballs and chase them around the arena to ram them into the snow.

The most interesting aspect of the fight is how Tyalmath uses perspective to convey the illusion of depth, jumping up "towards" the screen and becoming bigger or smaller depending on how close he is to our own world. It's an impressive visual effect even on the original PC-88 hardware, but it also betrays something about Ys II: this game is much more an aesthetic showcase for the computers and consoles it was published on than it is a mechanically sound game. This is far from the last boss in Ys II meant to show off hardware power, but it is one of the more blatant.

Fortunately, boss #3 marks a significant upswing over what came before.

Tuesday, April 9, 2019

Designing Ys II, Vol. 1: Velagunder

Ys II: Ancient Ys Vanished—The Final Chapter was a much younger game when Ys I & II first debuted. A common misconception even among Japanese players was that Ys II wasn't planned in advance, but was made as a separate project in response to the first game's financial success. Iwasaki himself debunked this in his Untold interview:

As I noted at the beginning of this series, the focus of Ys II is on magical combat rather than physical. It's easy enough to see how the first Ys games fit together as two halves of a mechanical whole, but in this case the team's original vision may have been a little bigger than they could reasonably realize. There are six spells in Ys II, which gradually replace the Books in the player's inventory as the game progresses. Despite this variety, one spell dominates gameplay to such an extent that I would call it the defining mechanic of II: Fire.

In most RPGs magic represents an exponential escape from the linearity of melee combat, capable of targeting different elemental weaknesses, providing buffs and debuffs, healing party members, affecting speed, and even expelling enemies from battle entirely. In Ys II magic serves to simply grind the flow of the bump combat system to a halt. This is exemplified by the first boss, Velagunder, who is designed to teach the use of the Fire spell.

Velagunder is completely immune to physical weapons, so the Fire spell is the only means the player has to damage him. His pattern is the simplest of any boss in the first two games; Velagunder aligns himself with the player's position, pauses, and fires out a row of five shots with gaps between them. The player is to quickly step into one of the gaps, then step back out and shoot Velagunder straight in the chest with the Fire spell. Velagunder is only vulnerable immediately after firing, and done too early or too late the spell will simply bounce off him. So the player's strategy is to sidestep Velagunder's shots then stand there, mashing the magic button until one of their spells bounces off, and realign themselves with the gaps.

In direct contrast to the tense high-speed weaving-and-charging gameplay of the Dark Fact battle, the Velagunder fight is one where Adol is constantly starting and stopping. It's nowhere near "seamless," the seams are everywhere, and this transfers to the battles against random mobs where the player finds themselves coming to standstill in the middle of dungeons to mash magic into crowds of monsters.

While Velagunder contrasts strongly with Dark Fact immediately before it, it also contrasts with Jenocres, the boss that began this whole series. There's much more going on with the Jenocres fight, and the elements of it are easier to intuit; while Velagunder's immunity to physical attacks is foreshadowed by one of the sage statues the player finds, Jenocres used mechanics that were already established from the moment the player first set foot in Esteria, and the torches' layout in that battle gave them an opportunity to step back and learn the pattern without putting themselves at an immediate risk. Whether you look at Velagunder as an eighth boss or a first, it's not a pretty picture.

The next boss, while visually impressive and less mechanically offensive, continues to develop Ys' slow burn on magic in a direction that doesn't see real fruition until many hours later.

"In the history of Ys, it is said Hashimoto and Miyazaki made Ys I and Ys II as two parts, two separate projects. This is not true. The original plan for Ys included the contents of both Ys I and II. However, that would be too much content for the floppy disk capacity of the era, so they decided just to make the first half. Then, after Ys was a hit, the sequel was greenlit. [...] I know that when Hashimoto and Miyazaki made Ys I, they didn't know if they could make the second part of the story. If Ys I had not sold enough, then perhaps they could not have made Ys II. But Ys I had big sales, and they were able to finish it. This is true, but lots of people still believe Hashimoto and Miyazaki planned them as separate games.

I heard the truth from [Yamane Tomo/Amagi Hideyuki] and also I know because of the comments in the source code for the games. For example in Ys I, the final boss is Dark Fact, and his messages were cut. They were removed or "commented out". Originally in Dark Fact's messages, he says Feena is [REDACTED] and after defeating the player he will hire her as a maid. But this is commented out. Because if Miyazaki and Hashimoto had used that, then Ys I would not be seen as finished. Because no player would understand that - "Why?! Why is Feena [REDACTED]? And why does Dark Fact say that?" So Miyazaki and Hashimoto cut that message, and Dark Fact only says something like, 'Welcome, but you die here.'"

—Iwasaki Hiromasa, Ys I & II director & main programmer, The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Vol. 2, p. 99(Yamane and Amagi are the same person under a pseudonym; Yamane on the original Ys and Amagi on Hudson's remake. Incidentally, Dark Fact's messages were restored for the Famicom version.)

As I noted at the beginning of this series, the focus of Ys II is on magical combat rather than physical. It's easy enough to see how the first Ys games fit together as two halves of a mechanical whole, but in this case the team's original vision may have been a little bigger than they could reasonably realize. There are six spells in Ys II, which gradually replace the Books in the player's inventory as the game progresses. Despite this variety, one spell dominates gameplay to such an extent that I would call it the defining mechanic of II: Fire.

In most RPGs magic represents an exponential escape from the linearity of melee combat, capable of targeting different elemental weaknesses, providing buffs and debuffs, healing party members, affecting speed, and even expelling enemies from battle entirely. In Ys II magic serves to simply grind the flow of the bump combat system to a halt. This is exemplified by the first boss, Velagunder, who is designed to teach the use of the Fire spell.

|

| The player that reaches the first boss without having learned magic is in for a rude awakening. |

In direct contrast to the tense high-speed weaving-and-charging gameplay of the Dark Fact battle, the Velagunder fight is one where Adol is constantly starting and stopping. It's nowhere near "seamless," the seams are everywhere, and this transfers to the battles against random mobs where the player finds themselves coming to standstill in the middle of dungeons to mash magic into crowds of monsters.

The fact that Adol cannot move and use magic at the same time creates perpetual interruptions in the flow of play. Regular Fire spells have no functional cost when compared with Adol's bottomless supply of Magic Points, and the ability to hold enemies at bay while bowling them over with the knockback from the spell makes it disproportionately powerful compared to tackling them head-on. Weapons still matter, as the damage a spell deals is derived directly from Adol's Attack stat, but those weapons will rarely if ever meet flesh. The Fire spell can be further enhanced with the Eagle and Hawk Idol items found on in the game's dungeons, which add homing properties it, and the spell eventually grows even stronger as Adol levels up and becomes capable of plowing through multiple targets at once. Even if the player wanted to not to use this incredibly powerful mechanic, the bosses are explicitly designed to be invulnerable to everything but it.

Instead of creating a dynamic supplementary system, magic turned Ys II into a bad shoot-'em-up.

Most of the game's other spells aren't especially useful, either. The other five spells consist of Light, Return, Transform, Time, and Shield. Light magic reveals hidden doors in the bottom parts of the map by filling them with light, which is useful in the mines when you're still unaware of the mechanic—then it becomes trivial to spot them on your own. Return has a much longer shelf life, as it allows the player to warp to the entrances of specific safe zones like the villages of Ys, and so the player comes to depend on it well into the endgame.

Transform is probably the second most useful spell, as it turns the player into a monster, allowing them to both bypass enemies without fighting them, and talk to them for clues. This does carry the risk of the player not being strong enough to overcome the subtractive damage formula, as they need to gain experience points to finish the game, but it also acts as a built-in dungeon shortcut that lets the player simply turn on Transform when they need to get back to where they were after warping out mid-dungeon.

Time and Shield arrive so late in the game that there's almost no opportunity to use them, with the former being prohibitively expensive to cast and only working to stop basic enemies in their tracks, and the latter only being available during the final boss battle. We'll get to it eventually.

While Velagunder contrasts strongly with Dark Fact immediately before it, it also contrasts with Jenocres, the boss that began this whole series. There's much more going on with the Jenocres fight, and the elements of it are easier to intuit; while Velagunder's immunity to physical attacks is foreshadowed by one of the sage statues the player finds, Jenocres used mechanics that were already established from the moment the player first set foot in Esteria, and the torches' layout in that battle gave them an opportunity to step back and learn the pattern without putting themselves at an immediate risk. Whether you look at Velagunder as an eighth boss or a first, it's not a pretty picture.

The next boss, while visually impressive and less mechanically offensive, continues to develop Ys' slow burn on magic in a direction that doesn't see real fruition until many hours later.

Monday, April 8, 2019

Designing Ys, Vol. 7: Dark Fact

The final battle of Ys is perhaps its most iconic moment, and the culmination of everything the bump combat system represents. The player enters the 25th floor of Darm Tower armed with six of the seven Books of Ys, having only just learned the name of the black-cloaked man they've been chasing across Esteria, and just as soon as the player gets to meet Dark Fact they find themselves facing him in battle. The meeting with Fact is by no means short—dying and challenging him again may account for as much as an hour of the game's six-hour playtime. But unlike the encounters with Vagullion or Yogleks and Omulgun, the battle against Dark Fact never feels "cheap" or "unfair" to the player; they always know exactly why they died, how they could have avoided it, and what they need to do better to prevent that from happening again.

Let's break the elements of this battle down:

The battle with Fact having eroding terrain is its most important feature, as this is how Falcom incorporated into the final battle the field elements of continually adjusting Adol's position while running through new territory. By integrating this with the principles of making safe attacks, always having a line of retreat open, striking at offsets, and evading projectiles, the Dark Fact battle brings together the disparate elements of Ys into a concentrated high-speed finale. In the age of romhacks and superbosses that kind of design might be hard to appreciate, but in the context of this being just three years after players were first cutting down Ganon and slaying Dracula, it's an impressive body of innovations. If there is fault in it, it's that the boss as-is often doesn't last long enough for its battle theme to be fully played out.

The Action RPG as a genre hasn't really changed that much even between 2009 and 2019—the big names in town are Nier Automata, Monster Hunter World, Breath of the Wild, and Kingdom Hearts III, but the mechanics they're drawing on came about with the turn of the millennium. Their moment-to-moment play isn't so radically different from the lineage that informed them: Dark Cloud, Kingdom Hearts, and Phantasy Star Online, all codified the control schemes and standards that today's ARPGs depend on. Meanwhile the battle with Dark Fact in 1987 and '89 is night and day not just to Xanadu, but to the final bosses of games released in the very same years as Ys. We would be hard-pressed to find anything in the 80s that surpasses it from any genre, making Ys a fitting conclusion to the decade and the capstone of Falcom's work in this period.

...Or it would be, but there's a whole extra game on the disc.

Let's break the elements of this battle down:

- Dark Fact is a moving target, but his movement is not unpredictable like Vagullion. He follows a set path, tracing out what may be the worst figure-eight in the world across the arena. As they continue to rematch Fact, the player becomes better attuned to this pattern and intuits the best ways to connect with him.

- Every time the player successfully damages Fact, the tile they hit him on is destroyed. If the player is standing on that tile they die instantly, though it's easy to avoid. The resulting pits are impassable, so the more damage the player does to Fact the more ruined the arena becomes and the harder it gets to maneuver. Effectively planning around hitting Fact on the corners and edges early on will lead to the player's movement being less restricted as the fight progresses.

- Fact periodically sends out one to two fireballs that explode in eight directions. Like Nygtilger, this is an unequal fight; Fact can shoot in twice the number of directions the player can move, which is where much of the challenge comes from.

- Although Fact does not speed up, as the fight goes on he sends fireballs out with greater frequency, and the erosion of the arena creates a gradual loss of options for the player. In contrast to what came immediately before him, the final boss of Ys builds intensity as the clash continues. Urgency is placed on the player to escalate with the boss, doing what they've already learned to do but faster and more precisely. The convergence of multiple eight-directional shots from different parts of the screen and overlapping holes in the floor pressures the player into the tight gaps between "death zones," providing a small taste of the kind of gameplay that would later define the bullet hell genre in the late 90s and early 2000s. (Later remakes extend the comparison even further.)

"The name Dark Fact will be the scourge of all men to come! Ha ha ha ha ha ha! Oh you are brave, but you are also a fool! You have no chance without the protection of the Silver equipment!"This was an addition made as a result of many players of the PC releases not picking up on the supporting cast's hints that the Silver Sword, Shield, and Armor, all had to be worn together to damage him. The PC-88, X-1, and other Ys releases lacked such an overt explanation. Iwasaki originally wanted to have a second audio track prepared, where Dark Fact panics upon seeing Adol in the full Silver set, but memory restrictions made this impossible.

The battle with Fact having eroding terrain is its most important feature, as this is how Falcom incorporated into the final battle the field elements of continually adjusting Adol's position while running through new territory. By integrating this with the principles of making safe attacks, always having a line of retreat open, striking at offsets, and evading projectiles, the Dark Fact battle brings together the disparate elements of Ys into a concentrated high-speed finale. In the age of romhacks and superbosses that kind of design might be hard to appreciate, but in the context of this being just three years after players were first cutting down Ganon and slaying Dracula, it's an impressive body of innovations. If there is fault in it, it's that the boss as-is often doesn't last long enough for its battle theme to be fully played out.

The Action RPG as a genre hasn't really changed that much even between 2009 and 2019—the big names in town are Nier Automata, Monster Hunter World, Breath of the Wild, and Kingdom Hearts III, but the mechanics they're drawing on came about with the turn of the millennium. Their moment-to-moment play isn't so radically different from the lineage that informed them: Dark Cloud, Kingdom Hearts, and Phantasy Star Online, all codified the control schemes and standards that today's ARPGs depend on. Meanwhile the battle with Dark Fact in 1987 and '89 is night and day not just to Xanadu, but to the final bosses of games released in the very same years as Ys. We would be hard-pressed to find anything in the 80s that surpasses it from any genre, making Ys a fitting conclusion to the decade and the capstone of Falcom's work in this period.

...Or it would be, but there's a whole extra game on the disc.

Sunday, April 7, 2019

Designing Ys, Vol. 6: Yogleks & Omulgun

We arrive now on the doorstep of the endgame, at the worst boss of Ys I: Yogleks and Omulgun.

(Nobody knows which head is which, but I always assumed Yogleks was purple and Omulgun red.)

The idea behind the fight is fairly straightforward. Both heads float around the boss arena, bouncing off of the walls. Each head is surrounded by a ring of fireballs, one moving clockwise and the other moving counterclockwise, which slowly expand and contract as they orbit the bosses. In order to damage them, the player has to quickly dart between the fireballs as they get an opening, strike the head, and come out of the ring unscathed. To prevent the player from simply staying inside the ring, the heads magically swap positions every time Adol gets a hit in; only the red head is vulnerable to damage.

There are a number of issues with this fight. The first is that because the fireballs rotate in opposing directions, the head-swap means if the player doesn't correct their course immediately after making contact they'll run straight into the swapped head's fireballs as they try to exit the ring. The second is that it requires a level of pixel-perfect precision not found anywhere else in the game—Adol has to start charging while his sprite is still aligned with the lowest fireball of the two he's trying to squeeze between, and make minute adjustments to get out unscathed. The third problem is more an issue of the boss' comprehensive design: it gets easier as the fight goes on, rather than escalating in difficulty.

See, as Yogleks and Omulgun lose Hit Points, they also start to lose fireballs, one per every quarter of their maximum health taken off. Most video game boss fights escalate in challenge the further the player can make it, thus passing through one phase establishes they're ready for the next. With Yogleks and Omulgun, the player starts the fight able to handle the last phase, which results in a denouement when they finally get past the first two and the tension dissolves.

Most players take issue with Vagullion, but I would contend that Yogleks and Omulgun are the boss that really needed to be fine-tuned. They start out disproportionately difficult compared to the bosses before and after them, on a scale that one can't help feeling it was a mistake, and end up disappointing the player that actually sees their fight through to the end.

Of note is that Falcom's official user support query outright calls the boss impossible without the Flame Sword, which would otherwise be an optional weapon, and strongly recommends acquiring the Battle Armor and Battle Shield rather than relying on the Silver set. Their recommended strategy is to sit in the corner waiting for the red face to draw near before charging through it, as the middle of the room leaves the player too vulnerable to damage. As many players concluded back in the 90s, a riskier alternative is to charge the red one in the room's center as the two heads are converging and catch it a second time after the swap.

So we've just had two badly designed bosses in a row. It would have been entirely possible for Ys to have peaked at its fourth big battle and never fully recover. Thankfully, the final boss of Ys I is also one of the best bosses in any 2D video game.

(Nobody knows which head is which, but I always assumed Yogleks was purple and Omulgun red.)

The idea behind the fight is fairly straightforward. Both heads float around the boss arena, bouncing off of the walls. Each head is surrounded by a ring of fireballs, one moving clockwise and the other moving counterclockwise, which slowly expand and contract as they orbit the bosses. In order to damage them, the player has to quickly dart between the fireballs as they get an opening, strike the head, and come out of the ring unscathed. To prevent the player from simply staying inside the ring, the heads magically swap positions every time Adol gets a hit in; only the red head is vulnerable to damage.

There are a number of issues with this fight. The first is that because the fireballs rotate in opposing directions, the head-swap means if the player doesn't correct their course immediately after making contact they'll run straight into the swapped head's fireballs as they try to exit the ring. The second is that it requires a level of pixel-perfect precision not found anywhere else in the game—Adol has to start charging while his sprite is still aligned with the lowest fireball of the two he's trying to squeeze between, and make minute adjustments to get out unscathed. The third problem is more an issue of the boss' comprehensive design: it gets easier as the fight goes on, rather than escalating in difficulty.

See, as Yogleks and Omulgun lose Hit Points, they also start to lose fireballs, one per every quarter of their maximum health taken off. Most video game boss fights escalate in challenge the further the player can make it, thus passing through one phase establishes they're ready for the next. With Yogleks and Omulgun, the player starts the fight able to handle the last phase, which results in a denouement when they finally get past the first two and the tension dissolves.

Most players take issue with Vagullion, but I would contend that Yogleks and Omulgun are the boss that really needed to be fine-tuned. They start out disproportionately difficult compared to the bosses before and after them, on a scale that one can't help feeling it was a mistake, and end up disappointing the player that actually sees their fight through to the end.

Of note is that Falcom's official user support query outright calls the boss impossible without the Flame Sword, which would otherwise be an optional weapon, and strongly recommends acquiring the Battle Armor and Battle Shield rather than relying on the Silver set. Their recommended strategy is to sit in the corner waiting for the red face to draw near before charging through it, as the middle of the room leaves the player too vulnerable to damage. As many players concluded back in the 90s, a riskier alternative is to charge the red one in the room's center as the two heads are converging and catch it a second time after the swap.

So we've just had two badly designed bosses in a row. It would have been entirely possible for Ys to have peaked at its fourth big battle and never fully recover. Thankfully, the final boss of Ys I is also one of the best bosses in any 2D video game.

Saturday, April 6, 2019

Designing Ys, Vol. 5: Khonsclard

"Among the bosses of Ys I & II's Ys I, there's a very minor boss in Darm Tower called 'Khonsclard.' ('Rock' was a popular name among the staff.)

In fact, if you ask a player of the PC version to name the bosses, they'll say 'the first boss,' 'centipede,' 'bat,' 'mantis,' and 'face,' but it's rare to hear 'rock.' Instead they'll say 'Dark Fact' for the sixth boss.

Next to the surprisingly difficult mantis, faces, and maze of mirrors right after it, the strategy is surprisingly easy. Usually it's figured out right away, or with bad luck it might take two tries. It seems to leave a weak impression...or that's the kind of boss I thought it was, anyway. Truthfully in the PC Engine version of Ys I & II I felt it was a complete mistake."

—Iwasaki Hiromasa, "Game Developer Failure Teacher in Ys I & II"In a 2016 the hashtag #ゲーム開発しくじり先生 (#GameDevFailureTeacher) began trending on Twitter, with game developers sharing stories of design failures in games. The tag had branched out from #同人しくじり先生 (#DoujinFailureTeacher) where doujin content makers had shared their own stories, which itself was responding to the popularity of the TV program Shikujiri Sensei - Ore Mitai Naru Na!! ("Failure Teacher - Don't Be Like Me!!") a variety show where various professionals showcased their failings as an example for others to learn from. Ys I & II director and main programmer Iwasaki Hiromasa chimed in on his blog, Colorful Pieces of Game, to recount a story from his end—his efforts to rebalance the game's fifth boss, Khonsclard.

"When I was doing debugging and balancing, I was bothered by how weak Khonsclard was.

It was always a free win.

But when I looked at the source code, the HP, Attack, and Defense values were fine, so I thought it was just easy because I already knew the strategy.

Why did I think the numbers were wrong?

Since you can see the boss' HP in the first place, that couldn't be it. And the damage formula is so simple it wouldn't be easy to make a mistake.

Except for Darm, the actual damage formula is as follows. (Darm uses a unique process with a special offensive and defensive table.)

- Damage dealt = Adol's Attack Power - Enemy's Defense Power

(Defense Power is basically the sum of of equipment. After that ring modifiers and the rest are applied.)

- Damage received = Enemy's Attack Power - Adol's Defense Power

With this terribly simple formula, standard parameter balance is created by looking up the boss' Attack and Defense Power using Multiplan. The balance between "face" and "mantis," there's nothing off about the numbers there.

That's why even though I thought 'Doesn't it seem too easy?', since it wasn't a bug, and nobody's going to complain if it's weak, and there were a ton of other bosses and goons to balance...I naturally turned my attention to bugfixing, and reducing the ready-to-burst memory. With so much to do, I just said 'well, whatever' and let it be.

I feel bad saying that, but I figured that because the strategy being easy wasn't a mistake, and it was such a forgettable boss, it wouldn't be a big deal even if it was a little weak.

(Actually, the PC Engine version's balance got various complaints from PC version fans, but nobody ever said 'the rock is too weak.')

So Khonsclard stayed a free win, and the master copy for the Japanese release was submitted."—Iwasaki Hiromasa, "Game Developer Failure Teacher in Ys I & II"Of Ys I's seven bosses, Khonsclard stands out for its lack of presence. Its basic pattern is to float towards Adol and spew rocks in a radial pattern, with significant gaps between them for the player to weave through. It's the only boss in the first game where Iwasaki felt the need to adjust its actual stats in the transition from Japan to the United States, gaining 6 points of Defense to increase the number of hits the player needs to destroy it.

"And then it was 1990.

I returned to Hudson in Hokkaido to begin work on the international version, but first I decided on three things.

- No rewriting the title. Just use all of it as-is. It's already in English, after all.

- Rewrite all of the confusing parts of the scenario. Since the original isn't sacred, it could be thoroughly revised.

It became crucial to discover any mistakes and to rebalance the product.

- Balance it for American tastes—punchy and hard.

We decided to adjust the overall difficulty level for an American audience, adjusting the experience points so that the game would not be as easy as the Japanese version. At the same time, I decided to double-check that weakling Khonsclard. With all that in mind, I read through the source code and found an outrageous mistake.

In addition to the boss' HP, Attack Power, and Defense Power, they actually have one additional standard parameter. That would be the time between receiving one instance of damage and the next.

At the same time a boss receives damage, a counter is set for its invulnerability, during the specified VSync. For example, if the counter is set to 30, it will be invincible for approximately 0.5 seconds, and conversely, if it is set to 3 the boss will be damage-able after 0.05 seconds.

And of course there's no memory available, and no reason to have these kinds of numbers as some easy-to-understand table, so naturally the whole thing was set in a special boss program one at a time, but the variable I set was a huge mistake.

(It would be tempting to say that it's not serious, but it really is. The "IDA address" orders are 3 bytes + the place where the data goes is 1 byte so the total is 4 bytes, but the IDA # variable is 2 bytes. It was incredibly important that we reduce the size by 2 bytes...otherwise there wouldn't be enough memory.)

Although I don't remember the exact numbers well, I think the standard value was 30 (so, once every 0.5 seconds) while I faintly recall this one being 3.

The rate of damage received was 10 times normal, so it died it extremely quickly."

—Iwasaki Hiromasa, "Game Developer Failure Teacher in Ys I & II"The solution to Khonsclard's fight is to run towards its rocks rather than away from them; to chase its clockwise motion and bump along the sides of the boss' shell to damage it, thus staying right behind the boss' line of fire rather than in front of it. Of course that level of precision is extremely difficult with four-directional movement, so the player is likely to take damage while executing this strategy, but even when slightly below the intended the level their output exceeds Khonsclard's. In theory, the boss is meant to encourage the player to chase the backs of attacks rather than run from their fronts, which plays into the boss that follows. But in practice, Khonsclard is kind of a mess.

Khonsclard is made up of a scarlet core and a body of rocks levitating around it. Ordinarily, a player would conclude that a boss made up of a core surrounded by debris would have the core as their weak point. There's a good deal of precedent for this: the enemy ship in Star Castle, the Big Core in Gradius, and Mother Brain of Metroid. With Khonsclard, the solution is completely counterintuitive—the debris is the vulnerable part and the core deals damage, with the optimal strategy being to run multiple complete squares around its body. It's a perhaps-unfortunate reality that games can't just be internally consistent, they have to exist in relation to the world around them, and this is where Ys fails to take into account everything else that's out there. It's not exactly surprising that the battle is so forgettable when it plays out like this and ends in seconds.

Nonetheless, it could be worse. Khonsclard was just forgettable; what follows after is actively malicious.

Labels:

action rpg,

adol christin,

analysis,

darm tower,

falcom,

game design,

hiromasa iwasaki,

hudson soft,

iwasaki hiromasa,

khonsclard,

pc engine,

rpg,

turbografx-16,

video game,

ys,

ys i & ii

Friday, April 5, 2019

Designing Ys, Vol. 4: Pictimos

The time between Vagullion and Pictimos is vast. In that time the player climbs and retreads nine floors, loses all of the Silver equipment, regains the Sword and Shield, gains five levels, and faces off with some incredibly dangerous enemy ambushes. Thus when the player sees the telltale entryway and the accompanying crest of Ys for the first time in several hours, their first instinct will be to save. This instinct is entirely justified.

Pictimos follows a set of rules rather than a distinct pattern. The boss can only move horizontally, and can have up to three sickles in play at a time, which follow a boomerang motion out to the walls of the arena and then return to the main body. Unlike the last two bosses, Pictimos deals no contact damage. The sickles home in on whatever position Adol is standing in at the moment they're fired; thus the player is pressured to put distance between themselves and Pictimos until it sends out the first sickle, then make a run for the main body as it sends out the next two, ideally outpacing all three of them and having enough time to score multiple hits against it.

Like Vagullion, Pictimos cannot be wholly predicted, as the motion of its main body is subject to random determination. Of the bosses faced up to this point, Pictimos comes across as the best-designed: it rewards observations of its parameters and movement, but has enough variation that the progression of the fight can be unpredictable. In the same breath, it's not wholly subject to the whims of the RNG. It also introduces another recurring play element that becomes pivotal both to the final battle of Ys and to Ys II as a whole: projectiles. The use of homing projectiles sets the stage for the later games' danmaku-like attack patterns, and while needing to evade three sickles at once is a significant step up from past boss battles, it's not so far removed from evading the monsters guarding the Silver Shield that it becomes overwhelming.

If only the next two bosses were so well-made.

Thursday, April 4, 2019

Designing Ys, Vol. 3: Vagullion

Most games would give the second-strongest weapon in the game to the player in the final dungeon, or shortly before entering it. Ys gives it to them less than halfway into the game.

There are two immediate reasons the player needs to explore the Mines of Esteria. The first is to acquire the third Book of Ys, and the second is to acquire the Darm Key necessary to open the way to the final three books. In addition to these, the Mines are where the game's antagonist hid the Silver Armor required for the final boss, and where the player can find the Roda Seed. This last item is what enables them to speak with the massive Roda Trees on the overworld, which will eventually let the player dig up the Silver Sword from within their roots.

While the player can enter Darm Tower as soon as they have the third book and the corresponding key, doing so locks them off from ever returning to Esteria. To ensure that the player has all of the Silver equipment before proceeding, the last boss faced before entering Darm acts as an equipment check—in other words, it's supposed to be impossible to defeat without the Silver Sword, Silver Armor, and Silver Shield. And for some, it's just impossible to defeat in general.

While simple in theory, there are several wrinkles to executing this strategy. First, while Vagullion is balanced around level 17, these are the player's naked stats at that level:

HP 85And these are Vagullion's stats:

ST 42

DF 35

HP 150For comparison, these are the player's stats with the fairly-average setup of Talwar, Small Shield, and Reflex Armor:

ST 75

DF 56

HP 85Vagullion's numbers are dramatically inflated for the purposes of the equipment check, and even with the Silver equipment the bat's output is devastating:

STR 58

DF 45

HP 85Vagullion goes from taking off a third of the player's Hit Points with each attack to shaving off 11%, but his swarm is also designed to get in two to three hits every time it makes contact, which provides the player with very little room to learn the boss' pattern before eating a Game Over. The player takes 12% off Vagullion with each hit and can bump that up to 24% with the right positioning, so they only need five clean hits to end the battle, but getting those hits in can be difficult because of one other property—Vagullion can feint the player.

ST 74

DF 67

The swarm is not required to reform unless the player is sufficiently far away. Thus the player that tries to simply pull away and loop right back, expecting the converging swarm to become a vulnerable Vagullion, gets a nasty surprise when it stops reuniting and instead begins chasing a player that's walking right into its trap. The probability of Vagullion feinting is determined by how far Adol is from the boss when it starts reforming, which director Iwamasa later recalled as being an addition to Vagullion's pattern created by Hasegawa Hiroshi, the second main programmer of Ys I & II. This behavior discourages the player from puppyguarding the boss, and introduces an element of randomness to its pattern that prevents it from being the exact same fight every time.

The combination of high stats, stringent equipment requirements, semi-random attack pattern, brief phases of vulnerability, and contact damage, all make Vagullion one of the most infamous bosses in Ys. It's not the most difficult boss found in the duology, but it is the one that claimed the most casualties in terms of unfinished playthroughs. It's difficult to say if the boss was supposed to be that hard—but at least when rebalancing the game for its "definitive" overseas release, Iwamasa did not see fit to make any adjustments other than the pattern changes Hasegawa came up with, whereas at least one later Ys I boss saw its stats modified and almost all major encounters of Ys II got an overhaul.

Labels:

analysis,

falcom,

game design,

hasegawa hiroshi,

hirosaki iwamasa,

hiroshi hasegawa,

hudson soft,

iwamasa hirosaki,

pc engine,

that one boss,

turbografx-16,

vagullion,

ys,

ys book i & ii

Wednesday, April 3, 2019

Designing Ys, Vol. 2: Nygtilger

This allows each boss to be balanced for a specific point on the level curve, but because of both this and the subtractive damage formula, low-level runs range from impractical to impossible. Players can usually only function at the exact level specified for each area. The first boss of Ys is balanced for level 4; Nygtilger is balanced for level 10.

That's a significant gulf in experience, and it's facilitated by the layout of the first big dungeon. The player's progress throughout the Shrine relies on thoroughly combing the place over. None of the other treasure chests can be opened until they have the Treasure Box Key from the second basement floor, and Nygtilger's lair is double-gated behind doors requiring both the Ivory and Marble Keys, which are in locked boxes on the third and second basements. The Marble Key is further behind a door that can be only accessed with the Mask of Eyes, which can be found on the first floor but also requires the Treasure Key.

This model of progress—a kind of item checklist the player is gradually filling as they progress—is among the oldest tricks in the developer's book, akin to the item puzzles of Zelda or ability requirements found in Metroid. In Ys it's implemented with a specific purpose for how the game should play moment-to-moment: the continual retreading of past floors serves to bring the player in contact with more wandering monsters, which respawn the moment the player scrolls them out of view, building their character level up high enough in time for them to arrive at Nygtilger. As a resulting, there's no grinding. The player is already as powerful as they should be as soon as they arrive on the boss' doorstep.

The "centipede" as players so often call it is designed to draw the player into a chase. The head is the only part that can damage them, while every other segment is vulnerable to Adol's sword. Thus the player chases Nygtilger's tail while its head chases their own, causing the two to circle one another until they make a misplay and must break apart to find a new position to attack from. The fight contrasts strongly with the patient wait-and-charge pattern of Jenocres, and serves to reinforce a lesson about the nature of dungeons versus overworld areas. While the player was free to exit Jenocres' battle anytime and recover their Hit Points in the hallway, leaving Nygtilger's fight won't trigger the passive health regeneration because they're inside a dungeon area.

The battle can be over in seconds or minutes, but the longer it drags on the more likely the player is to fall, for one simple reason: Nygtilger is faster than them. This is the first of several unequal fights in Ys. In general, the difficulty of the game comes from how uneven the boss design is. Major enemies simply have more resources at their disposal, whether that comes in the form of greater speed or more angles of attack than the player. The simple fact that the odds are against them in protracted battles creates great tension for the player, but at times it can also be a weakness as one of Ys' strengths is its soundtrack, and because of these design sensibilities it can be rare to hear certain tracks ever fully played out.

Once the player has Nygtilger's vulnerabilities and pattern down, the fight becomes simple. However, this is the last fight where knowing such information can grant an easy victory. The next major battle serves as one of the defining gameplay moments of Ys I, and the reason that many players give up without seeing the game through.

Vol. 3: Vagullion

|

| Nygtilger in the Ys anime series. |

Labels:

action rpg,

adol christin,

analysis,

centipede,

falcom,

game design,

hirosaki iwamasa,

hudson soft,

iwamasa hirosaki,

nygtilger,

pc engine,

role-playing game,

turbografx-16,

ys,

ys book i & ii

Tuesday, April 2, 2019

Designing Ys, Vol. 1: Jenocres

"Falcom's Ys series was one of the biggest games in Japan, while Hudson's version of Ys for PC Engine was regarded as one of the best conversions."

—Iwasaki Hiromasa, Ys I & II director & main programmer, The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Vol. 2, p. 96

In the context of 1989, Ys I & II must have seemed overwhelming. It was among the earliest of the PCE/TurboGrafx's RPG library, preceded only by the first Tengai Makyō game, Necromancer, and Dungeon Explorer. (Which admittedly has more in common with Gauntlet than Dragon Slayer or Tritorn.) While sales numbers for PC Engine software seem lost to time, it's clear from the prominent featuring of Ys in Gekkan PC Engine and other gaming magazines that this was a very significant title in its moment, and we know from Falcom's PC Engine-exclusives that all of the company's games performed well on the console. The PC Engine was something like the Vita of its day, and Falcom was still Falcom, producing games well into 1995 for a system that was abandoned by its own manufacturer in '92. Without this Ys port, we'd have never arrived at Legend of Xanadu or The Legend of Heroes.

|

| Gekkan PC Engine #11, featuring an "Ys Adventure Report" on its cover story. |

You flick the power switch and there are twenty times the colors on-screen.

And not just more colors, but Red Book audio, animated cutscenes, and voice acting—by the likes of professional seiyū Ginga Banjō (Mobile Suit Gundam, Fist of the North Star) Watanabe Naoko (Dragon Ball, Saint Seiya) and Mori Katsuji. (Gatchaman, Tekkaman) After Tengai Makyō this was only the second time an RPG had featured voice acting, and attempted to lip-synch its audio with the dialogue. Its international localization was incredible for the year it came out in, being the first English-language game to have an actual voice director and primarily professional cast, with key roles played by 80s TV animation actors like Michael Bell (G.I. Joe, Superman) and Alan Oppenheimer (He-Man, Transformers)—and by a pre-Jimmy Neutron Debi Derryberry, still early in her career.

The disc that first went out to retailers some thirty years ago wasn't just the proof of concept for the format, it was the state-of-the-art. Director and main programmer Iwasaki Hiromasa later remarked in The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Vol. 2 that before Ys, everyone believed the CD-ROM format was slow; after Ys, "only a bad developer would make a really, really slow game." (Untold 89)

|

| Same year, vastly superior presentation. |

Iwasaki Hiromasa was not involved in the original production of Ys, but fell in love with the games on PC while working at Hudson Soft, and was later approached by Hudson Company Director Nakamoto Shinichi to port it to PCE. He was granted the incredible opportunity to work with the fully-commentated source code of the original games—preservation practices at Japanese software companies are infamously poor, as even up through 2002 major developers like Square were clearing out their data to make room for the next project as soon as the previous one was finished. No one had remakes in mind in this era, yet because of Falcom's multiplatform release schedule across many different desktop standards, the tiny studio retained the Ys development assets in time for their definitive port.

It was Iwasaki who came up with the idea of bundling Ys I & II together into one unified game, chose Hasegawa Hiroshi of AlfaSystem as the compilation's other main programmer, and as the game's director also assumed responsibility for casting its voice actors, picking them based on anime VHS tapes he had rented out from the first floor of Hudson's Sapporo Sankei building. (Untold 92 & 94) Iwasaki and Hasegawa took certain liberties with Ys—liberties that director Hashimoto Masaya and scenario writer Miyazaki Tomoyoshi would later give their stamp of approval, declaring that Ys Book I & II was the game they "want[ed] to create." (96)

"You need to understand that in Japan, Ys I and Ys II are really, really, really famous games. Everyone loves them. But I felt the text in the originals was not good for explaining the background to the games. I couldn't change it for Japan though, because they're really famous, and if I change something for Ys: Book I&II, if I changed some text, perhaps a lot of players would complain about that. [...] But I knew that Americans did not know this game, and I wanted to explain it. About the background, characters, and everything. So I changed a lot of text. [...] So I think that Ys: Book I&II for the USA is really the best version—for me anyway."

—Iwasaki Hiromasa, The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Vol. 2, p. 95The changes Iwasaki made were extensive. Virtually every common monster had its Defense and Experience values raised or lowered to subtly adjust the game's challenge and level curve. One late-game Ys I monster, the Riffligan, had its Hit Points, Strength, and Defense decreased from 150 to 135, 106 to 98, and 55 to 23, in order to prevent an underleveled player from becoming stuck once locked inside Darm Tower. Overall the amount of grinding demanded for Ys I was reduced, while individual battles in both games became more difficult. Iwasaki also introduced level carryover between the two books, with Adol's level being automatically raised to 34 at the start of II if it was lower. These decisions were informed not just by Iwasaki's experience as a game developer, but as a player—the decision to raise the fifth boss, Khonsclard's, Defense from 83 to 89 stemmed from his personal suspicion that it was too easy, and by how players tended to forget Ys I had a boss between Pictimos and Yogleks/Omulgun.

Ys as a whole is built atop a framework that dates back to 1984's Dragon Slayer and Hydlide, the "bump combat system." (Usually referred to in Japanese as 体当たり taiatari "tackling.") Essentially, the directional pad is the only input the player uses to battle; they joust at enemies on the overworld and bosses in their arenas, ramming through them to deal damage. Ys' implementation of the system is more refined than its predecessors, as the player can avoid mutual damage by hitting their target at an offset rather than head-on. This is a conceit pulled from Xanadu, but the hitboxes in Ys are less ambiguous than in Xanadu. Moreover, Ys has two different speed settings to turn the game into a much faster and tenser experience.

The bump combat system is generally unpopular with today's players, as it's less familiar than having a dedicated button for swinging a weapon in the style of Zelda or Terranigma, but there are a number of advantages to it. Going with bump combat allowed Falcom to create high-speed battles that simply couldn't exist in the 2D Zeldalikes, where the player had to stop moving to mash their attack button once an enemy was rendered vulnerable. Ys I is that rare 80s game to be totally free of button mashing, as the constantly moving enemies require the player to make on-the-fly adjustments to their angle of attack if they want to avoid damage. It's a system that on the surface sounds too rudimentary and crude to have any depth, but in practice requires finesse to do well. Ys is accessible, but it's not easy.

Aside from the gameplay advantages of it, the bump combat system also expedited the porting process—every computer has a set of arrow keys, and every console has a directional input. It's not a perfect system, as the game's lack of diagonal movement results in awkward "stair-shaped" motions when the player transitions from horizontal to vertical input, but as we'll soon see, the bump system has a vast amount of design space available, not all of which was realized within the first two games.

With Xanadu Falcom had innovated a system made up of swordplay and spell-slinging, assigned to the arrow keys and spacebar. Ys picks up where Xanadu left off, but focuses on one half of the system at a time. Ys itself is a story divided into two volumes, with the first book focusing on the melee combat through the directional pad and the second book emphasizing magic through the I button. Those books are themselves divided into two further halves. The first half of Book I sees the player traveling the open fields of Esteria while the second half has them climbing the 25 floors of Darm Tower, and the first half of Book II encompasses the ascent from the foot of Ys up through the frozen tundra and smoldering caverns of the island, before ending with Adol's adventure through the labyrinthian Shrine of Solomon and its interconnected canals.

The journey through Ys Book I is about tracking down the six Books of Ys to discover what happened to the titular vanished island and find a way to subvert the crisis befalling the present-day land of Esteria, but from the player's perspective these are just reasons to set foot in their next sword-and-sorcery fantasy. The six volumes act as the governing structure around the game: when the player has all six, the credits roll. Each book save for the last is guarded by a boss, with volume six having two consecutive bosses blocking the player's path. These bosses will be our main subject of content analysis, as dying and challenging them again accounts for most of the game's playtime.

Esteria is broken up into four principal parts: the towns of Minea and Zeptik, the Shrine, and the abandoned mines. Separate from these is Darm Tower, which the player cannot exit once they've entered. Ys can be loosely described as open-world, as the player's primary obstacle to exploring these areas is the strength of the monsters within them. Unlike more recent such games (Breath of the Wild) skill can't totally overcome those monsters because Ys uses a subtractive damage formula, so damage can be 0. (Attack - Defense = Damage.)

Aside from the monsters themselves, there are several elements in Ys I that serve to pressure the player into following a general sequence and discourage them from exploring specific dungeons until others are cleared. The Treasure Box Key is necessary to open all of the treasure chests in the first half of Book I except for the chest it's found in, and the key itself is nested two floors down into the Shrine, which the player can only access if they have the Tovah Crystal from the old woman in Zeptik village, which requires the player have already spoken with the fortune-teller in Minea and acquired a sword, shield, and set of armor. Without the key the player can't effectively explore the mines, thus discouraging them from acquiring the third Book of Ys before the first two. This type of item placement pushes the player to follow a loose sequence, so that by the time they get the key needed for the other areas, they are already deep enough in the Shrine that they're better off finishing the dungeon before backtracking to explore the rest.

Any player that gains entry into the Shrine will find their progress quickly halted by the first boss of Ys, Jenocres. Jenocres serves as the Barthesian threshold guardian standing between the Shrine's empty upper level and monster-infested lower floors. He does not attack the player directly, but instead teleports around the room, leading the player into the line of fire of one of his six torches. Each torch has a maximum range of about eight tiles, crossing just past the halfway point of the chamber. The flames can briefly meet, but if two flames touch then one of them will immediately recede, so that there is always at least one space to move freely between any two torches. Thus the player is challenged to watch and anticipate the torches Jenocres is luring them into, and find the one path that will let them ram Jenocres while still having the free movement to escape the torches unscathed.

Jenocres teaches the player several critical lessons:

- Unlike regular wandering monsters, the vulnerable parts of bosses do not deal contact damage.

- Charging at an offset still deals more damage than charging normally, which translates to less opportunities for the boss to deal damage. Even though there's no contact damage from a bad bump, there's still a penalty for poor execution.

- Evasion is just as critical as offense, and every attack one initiates should have an escape route out of it.

Ys has sometimes been positioned as a "beginner's" RPG, made to introduce players to the nascent Action RPG genre with an easier game, the idea being to eventually induct them into "real" games like Xanadu and Tritorn. While in the context of the PC-88 it's easy to see how that line of logic could emerge, it's doubtful for one overarching reason: Ys is hard.

Jenocres is the player's first major roadblock and the first thing that really threatens them with a Game Over. They will likely mount a dozen or so attempts before they finally nail his pattern down and do the wizard in. None of the bosses in Xanadu are that threatening on their own—sure you have the floaty jumps to work out, but the real threat to the player is the player themself, getting too greedy and bungling a run by killing too many enemies and not being able to level up the later weapons and spells. Actual Game Overs are rare in Xanadu. The big threat is just making the game unwinnable and being stuck in the dungeon forever. By contrast, in Ys death is lurking in every boss chamber with monsters that rival the best and worst of Zelda, Castlevania, and Legacy of the Wizard. It's a process facilitated by the game's save-anywhere and regenerating health features, and the player can actually leave Jenocres' room mid-battle to restore all their HP outside before heading back in to reset the fight, giving them the option to know when to fold 'em on battles that are too far swung in the opponent's favor. This boss is supposed to kill you again and again before you realize you can exit and restart.

And when Jenocres goes down, the game really begins...

Ys I: Ancient Ys Vanished Omen

Vol. 2: Nygtilger

Vol. 3: Vagullion

Vol. 4: Pictimos

Vol. 5: Khonsclard

Vol. 6: Yogleks & Omulgun

Vol. 7: Dark Fact

Ys II: Ancient Ys Vanished—The Final Chapter

Vol. 1: Velagunder

Vol. 2: Tyalmath

Vol. 3: Gelaldy

Vol. 4: Druegar

Further Reading

The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, Vol. 2 – Yakuza, Robots and the PC Engine, John W Szczepaniak, published by Hardcore Gaming 101

"Nihon Falcom – Ys Developer Interview," 1987, translated by Shmuplations

"Ys I and II Developer Interview," 1988, translated by Shmuplations

Colorful Pieces of Game (Japanese, old), Iwasaki Hiromasa.

Colorful Pieces of Game (Japanese, new), Iwasaki Hiromasa

Tuesday, January 15, 2019

How Dragon Quest created the Survival Arc

The player character's starting stats in Dragon Quest are determined by the first four characters of their name; each character had a hidden numeric value, the sum of those values would be divided by 16, and the remainder would be used to determine the player's starting stats and growth type.

Japan has two phonetic writing systems, hiragana (for native words) and katakana (for foreign words), as well as a third writing system called kanji used to compress long phonetic words into shorter logograms. (For example, byouki "sick" is 4 characters long in hiragana びょうき but only 2 characters in kanji 病気.) However, Dragon Quest only uses hiragana in its text, for several reasons: it costs less memory to store 46 characters than the 82 including katakana or 2000+ kanji would require, and because hiragana is the first writing system a Japanese child learns. This makes the game accessible to people of all ages. Thus Dragon Quest mapped the 46 hiragana characters and two punctuation marks (゛and ゜) to numeric values 0~15.

here--let's use an example to gauge relative player strength. The common boys' name "Touya" is written とうや in hiragana, and so is three characters long. Any unused space in a name less than four characters is treated as a 0. と is worth 10 points, う is worth 13 points, and や is worth 14 points. Added together that's 37, divided by 16 we get 2.3125 rounded down to 2, and to get the remainder we multiply 2 by 16 and subtract that from 37: 37 - 32 = remainder 5.

The remainder is then compared against a table that assigns Strength, Agility, Hit Points, Magic Points, and Growth Type based on the remainder's value. In this case, remainder 5 gives us 4 Strength, 3 Agility, 15 Hit Points, 4 Magic Points, and Growth Type II. There are four Growth Types in all, with each one having higher growth in two stats and lower growth in two others. (Think like Natures in Pokémon, but they affect four stats instead of two and apply to every level-up instead of just being a flat 10% increase and 10% decrease.) Growth Type II raises Strength and HP growth but decreases Agility and MP growth, making a beefy physical attacker with low defenses and low magic.

The hero in Dragon Quest learns their first spells at levels 3 and 4--Hoimi/HEAL and Gilla/HURT, Hoimi recovering 10~30 Hit Points and Gira dealing 5~12 damage. Focusing on the early game, our sample hero Touya is relatively well built for survivability, but that isn't the case for all heroes. The lowest possible starting stats in Dragon Quest come from "remainder 6" names; these names produce heroes with 3 Strength, 4 Agility, and 13 HP. Only names whose sum is 6, 22, 38, or 54 can cause this. (Names that come to mind are the female names Aoi, Kirino, and Sara, the unisex name Yuu, and the family name Rikino. Yuu is particularly notable because it's also a common nickname for Yuuta, Yuuto, Yuuko, Yuugo, Yuuichi...etc.)

The first objective of the player in Dragon Quest is to get to level 3 so they can learn Hoimi and thus have the stamina to travel far enough to reach the Roto's/Erdrick's Cave, and eventually Garai/Garinham. Since magic is inaccessible until that point, the player's relative difficulty is going to be based purely off of their physical stats. For our examples, Touya is a 4/3 Strength/Agility with 15 HP, while Yuu is a 3/4 Strength/Agility with 13 HP. Agility is used to calculate the Defense stat in Dragon Quest while also determining one's probability to escape from battle, with Defense being equal to [Agility / 2].

In general, the damage formula in Dragon Quest is:

(Attack - ([Defense / 2] + Armor Defense Bonus)) / 2 = DamageWith 1 as the lower limit. The fact that the bonus from equipped armor is applied after Defense is calculated for the player is important. The structure of this formula means that it generally takes four points in Agility to equal one point of damage reduction, and reductions from armor are four times as effective as reductions from level-ups. This is a very influential formula, one that was mostly reused in future Dragon Quest games and copied by games that tried to emulate its style, especially with regard to RPGMaker. Odds are if you've delved into the world of Japanese Role-Playing Games beyond just Final Fantasy, you've played at least one game that used this formula or a variant of it.

|

| The monsters of Dragon Quest will kill you with a smile. |

Slimes are 5/3 Strength/Agility with 3 HP, Slimebeths are 7/3 Strength/Agility with 4 HP. If the player ventures to the south they'll be in the northern part of the Rocky Mountain Cave region and won't be able to pass over the mountain tiles, but they will start to encounter 9/3 Drackies with 6 HP. Closer to Roto's Cave they'll run into 11/8 Ghosts with 7 HP, and nearer to Garai 11/12 Magic-Users/Magicians with 13 HP. Not only are they physically stronger, the Magic-Users can cast Gilla, which deals a flat 3~10 damage irrespective of Agility.

Remember, at this point Touya is 4/3/15 and Yuu is 3/4/13. Unequipped both of them will deal 1 damage to any of these opponents, because the minimum damage output in Dragon Quest is 1, while on Critical Hits Touya will always instantly kill a Slime and deal 1~4 to a Slimebeth. Touya will take 1~2 damage from Slimes, 1~3 damage from Slimebeths, while Yuu will always take 1 damage from Slimes and 1 or 2 damage from Slimebeths. These enemies are both easily survivable since any hero we make will always have a 1:1 damage trade with the monsters each turn while having 3~5 times the number of Hit Points.

The problems come in when you factor in the Drackies for the first time. A Dracky deals 2~4 damage while always taking 1 outside of crits, outpacing both heroes 1:2 or 1:4, taking between four and eight turns to defeat the player depending on variance while the player needs 6 turns of normal damage to defeat them. Critical Hits only have a 1/32 chance of occurring, meaning the player has a ~1% chance to take out the Dracky in two turns and not much other hope. Ghosts likewise outpace the player 1:2 or 1:5 and Magic-Users can go as high as 1:10.

This is the first Survival Arc. The only monsters in the game the player can survive against when they first turn the game on are Slimes and Slimebeths. This is a mathematical fact. The only means of changing this fact is gaining levels and/or equipment, and the +4 Defense Leather Armor costs 70 Gold Pieces out the gate. Both Slime variants award just 1 Experience Point on defeat, but Slimebeths also give 2 GP instead of 1. The player needs 7 XP to reach level 2 and 23 XP to reach level 3, which means that the player's first real objective in Dragon Quest is to run laps around Ladutorm Castle fighting 23 Slimes while running from Slimebeths to conserve their HP. (Grinding for the 60 GP Club for +4 Attack takes longer than grinding to level 3 even if the player purposefully only fights Slimebeths.)

Past authors have thrown up their hands at this point and plead "Why?"

This is the first Surival Arc, and it is a seminal moment in the history of Role-Playing Games for also being the genre's first grind. Not in the literal sense of being the first game to have grinding, but in the sense that this was the model of grinding emulated by a greater industry, the first grind played by millions, the grind that inspired Sakaguchi, Itoi, and Naka. But as Leeroy Lewin illustrates in discussing Phantasy Star, the Survival Arc is not meaningless no matter how it unconscionable it may be. The Survival Arc establishes the hostility of the world and how unwelcome the protagonist is inside of it; the hero's job is to perform a role fighting monsters, but at the outset of their adventure they can do so only inside a limited space in which the conditions are right for them to thrive.

The hero of Dragon Quest can only survive fighting Slimes and the occasional Slimebeth until he reaches level 3, Alisa/Alis of Phantasy Star can only profit from fighting Monster Flies/Sworms on the outskirts of Camineet--and encountering nearly anything else is a death sentence until her first level-up. The Warriors of Light in Final Fantasy are stopped cold if they try to fight Gigas Worms before Goblins, and Ninten of MOTHER/EarthBound Beginnings won't get far against Alligators if he doesn't stop to beat up some Hippies first. Each and every one of these games follows a delicate but soul-crushing sense of balance in which the player must slowly acquire strength in a hostile world where power rules absolute over all else. So it goes for Courageous Perseus, Mugen no Shinzou, and Xanadu.

The hero of Dragon Quest can only survive fighting Slimes and the occasional Slimebeth until he reaches level 3, Alisa/Alis of Phantasy Star can only profit from fighting Monster Flies/Sworms on the outskirts of Camineet--and encountering nearly anything else is a death sentence until her first level-up. The Warriors of Light in Final Fantasy are stopped cold if they try to fight Gigas Worms before Goblins, and Ninten of MOTHER/EarthBound Beginnings won't get far against Alligators if he doesn't stop to beat up some Hippies first. Each and every one of these games follows a delicate but soul-crushing sense of balance in which the player must slowly acquire strength in a hostile world where power rules absolute over all else. So it goes for Courageous Perseus, Mugen no Shinzou, and Xanadu.

Over the course of a traditional Japanese Role-Playing Game the stat paradigm governing the Survival Arc shifts. The oppressor-oppressed relationship between the monstrous world and the player character transforms into one of predator and prey. The endgame of any RPG has the player hunting down rare monsters rather than hiding from them; chasing Grand Kuwagamon parties in the Destroyed Belt of Digimon Story for that maximized 4000+ XP, or hunting the Jachol Cave Skull Eaters in Final Fantasy V for 5~10 Ability Points. This curve reflects the development of the party into a functional and destructive force in the world.